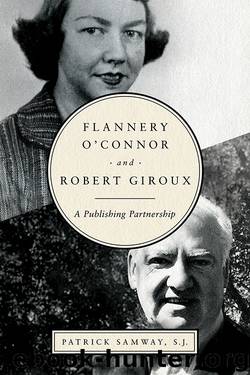

Flannery O'Connor and Robert Giroux by Patrick Samway S.J

Author:Patrick Samway, S.J.

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Notre Dame Press

Having located Langkjaer in Denmark, Fitzgerald interviewed him for her biography of O’Connor; Langkjaer, in turn, shared with her the twelve letters that O’Connor had sent him after he departed from the South. Fitzgerald noted a qualitative difference in these letters, which reveal a depth of feeling seen nowhere else in O’Connor’s correspondence. She quotes a handwritten postscript in one such letter to Langkjaer as indicative of O’Connor’s feelings for the young Dane: “I think that if you were here, we could talk for about a million years.” The poignancy of this revelation lies in its timing, for her letter to Langkjaer was sent shortly before the arrival of his own letter to her announcing his engagement to marry. O’Connor, Fitzgerald notes, instantly withdrew into her customary reserve, and the letters sent to Langkjaer thenceforward were warm but very correct in their southern manners.26

One of the letters quoted by Bosco from O’Connor to Langkjaer, dated October 17, 1954, shows a vulnerable side of O’Connor that she had never before revealed: “You are wonderful and wildly original and I would probably think you even more so if I didn’t still hope you will come back from that awful place. . . . Did I tell you I call my baby peachicken Brother in public and Erik in private?” It seems that O’Connor and Langkjaer had decided not to break off their relationship after a lengthy discussion; rather, on their last night together, they kissed a few times as he told her of his summer plans.27 Her father, her editor, and now her boyfriend (to apply a word she probably would not have used), had left her. She concluded another letter to Langkjaer, “I haven’t seen any dirt roads since you left & I miss you.”28 Although O’Connor had invested so much of herself in writing this story, she was able to distance herself from the immediacy of the experience, focusing more on the story’s literary qualities. One could well ask if her relationship with Langkjaer might be one of multiple reasons why O’Connor does not depict mature single men or happily married couples in her fiction, though Paul Engle remembered one story she wrote earlier “involving a scene between a young man and a young woman about to make love.”29 Once they had a chance to discuss the story in private, Engle concluded, “It was obvious that she was improvising from innocence.”

After Langkjaer’s departure, any consolation, however small, would help. When the finished books arrived in early May 1955, O’Connor wrote to Carver saying that she liked them. She noted that the first chapter of her projected novel, “Whom the Plague Beckons,” had been sold to New World Writing (the title was later changed to “You Can’t Be Any Poorer Than Dead”). Carver, for her part, felt it important to meet personally with O’Connor and see how they could work together. After talking with her by phone, she started making arrangements for O’Connor to meet other people in the New York publishing world, even planning for her to make a foray into public television.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14507)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14075)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12028)

Becoming by Michelle Obama(10026)

Educated by Tara Westover(8054)

The Girl Without a Voice by Casey Watson(7889)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5786)

Hitman by Howie Carr(5095)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5095)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4969)

Hunger by Roxane Gay(4928)

On the Front Line with the Women Who Fight Back by Stacey Dooley(4873)

Year of Yes by Shonda Rhimes(4757)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4325)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4274)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4110)

American Kingpin by Nick Bilton(3886)

Patti Smith by Just Kids(3777)